Why Fear Isn’t the Adversary, It’s the Mind’s Most Misinterpreted Signal!

Fear ranks among the most instinctive and occasionally disconcerting emotions we may feel, yet it can be navigated in numerous ways.

Consider, for instance, the varied reactions one can exhibit toward ghost tours: while some might flinch at the idea, others might find excitement in it.

In terms of self-awareness, psychological mechanisms intertwined with brain chemistry illuminate how and why certain individuals respond differently to fear.

In this article, we concentrate on the:

– Effect of fear on self-awareness,

– The methods by which mindfulness can be applied to manage fear positively, and

– How this comprehension can be harnessed holistically to foster growth, connection, and resilience?

Brain’s Fear Circuitry

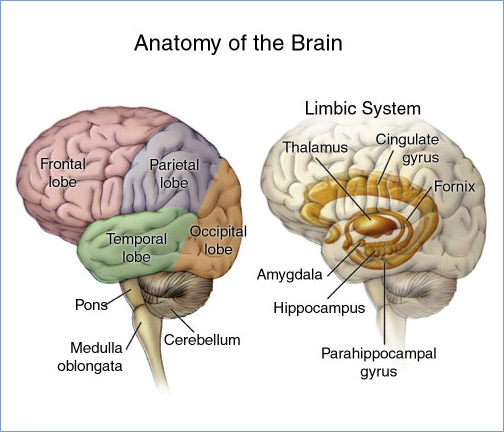

The fear of the unknown or unexplained is an ancient emotion potentially originating from various elements; in this instance, we will examine the amygdala.

The amygdala is the brain segment responsible for identifying fear or any type of possible danger. Upon recognizing a potential threat, this area prompts the fight-or-flight response, signaling the hypothalamus to release stress hormones.

Nonetheless, as we have come to grasp the principles of the amygdala, it also seems that genetic variability plays a role in individual responses, and how the prefrontal cortex manages it.

Certain individuals swiftly and efficiently handle specific threats to their safety, allowing them to rationalize and maintain control. Conversely, a portion of the populace has hyper-reactive amygdalas that respond sensitively even to minor threats.

Mitigating or minimizing exaggeration is typically rooted in the degree of cognitive control a person possesses. This control presents itself in various manners; in some situations, fear can be transformed into exhilaration, while in others, it morphs into something intensely gripping.

Dopamine Connection

What connects bungee jumps and horror flicks? Dopamine.

When we engage in novel, high-energy situations, the brain releases a mix of chemicals:

– Dopamine — pleasure and reward

– Adrenaline — energy and vigilance

– Endorphins — pain relief and ecstasy

Some individuals exhibit heightened sensitivity to dopamine, positioning them as thrill-seekers. For these individuals, fear does not represent stress — it becomes a source of entertainment. It transforms into an exhilarating break from everyday dullness, delivering a biological “high” that’s difficult to overlook.

Safe Scares: Importance of Context

The essential reason we can find enjoyment amidst fear lies in the security that accompanies it. The physiological response to fear in settings like a haunted house, horror movie, or amusement park ride includes an increased heart rate and perspiring palms. Yet, concurrently, the person’s mind remains clear and at ease.

This dynamic creates a seamless interplay in the body, while the mind experiences tranquility. In essence, a genuine sense of risk is necessary for an individual to genuinely experience fear.

Many individuals can leverage fear within a controlled environment as a training framework to boost their resilience, personal fortitude, and self-awareness. By confronting fear at a manageable level, one can learn how their body reacts to stress and how swiftly it can revert to a calm and composed state.

Our History With Fear

Fear has long been part of humanity’s narrative. Ghost tales and dramatic storytelling are time-honored forms of narrative that elicit fear. Humanity has harnessed fear to educate groups, encourage solidarity, and instill bravery.

These community rituals taught individuals to embrace fear, both in stories and on the battlefield, cultivating a collective sense of courage.

Over the ages, fear has transitioned from folklore to entertainment. Modern horror films, haunted attractions, and theme park experiences exemplify today’s adaptations of ancient fear-inducing methods. They allow us to confront fear within a controlled, secure framework, pushing our boundaries.

Shared Fear, Shared Connection

This is where chemistry intersects with community: oxytocin, the bonding hormone, surges when we experience strong emotions collectively. The more authentic the emotional arousal — like fear — the more potent the connection.

Consider first dates in haunted settings or friends sharing screams on a roller coaster. Those collective experiences circumvent mundane conversations and accelerate closeness. Our brains instinctively cultivate trust when we face threats together — even if the threat is artificial.

This concept is supported by Shelley Taylor’s “Tend and Befriend” theory, which asserts that during stress, individuals naturally seek social bonds to manage their emotional responses.

Why Some Avoid Fear?

Most individuals encounter some degree of fear, but it can be paralyzing for others. Those grappling with anxiety, hypersensitivity, or past traumas frequently endure overwhelming and unshakable fear responses. Their fight-or-flight mechanisms remain hyperactive long after